The primary theory of the intended iconography of the snail is that it is a personification of human cowardice. The snail could be a commentary on humanity’s cowardice, a symbol of the Lombards, or a medieval joke (see fig. Though the exact meaning of the motif is still unknown, art historians have established several theories. Occasionally the knight will be shown kneeling before the snail or a woman will be shown pleading with the knight to not attack the snail. The motif is characteristically shown with a knight, armed with a sword or lance, confronting a snail, whose “horns are extended and often pointed like arrows” (Randall, Lillian). This particular motif emerged in the margins of manuscripts and quickly entered the canon of medieval imagery. The motif of a knight in combat with a snail appeared first in the margins of Northern French manuscripts towards the end of the 13th century and persisted throughout the Middle Ages appearing in Flemish and English manuscript margins as well. The following articles will discuss two particularly interesting recurring motifs in medieval manuscript marginalia, the knight battling the snail and the monkeys and the peddler. The meaning behind marginalia may never be able to be fully understood, as it lacks the iconographic stability of more developed motifs and scenes, but as it is researched more historians can gain new insights into medieval society. One theory states that these images, which often showed recognizable members of society, such as monks or nuns doing inappropriate things, were a way for artists to satirize the strict social order. Much like other forms of art, marginalia formed a repertoire of themes and scenes that appear in many different manuscripts.

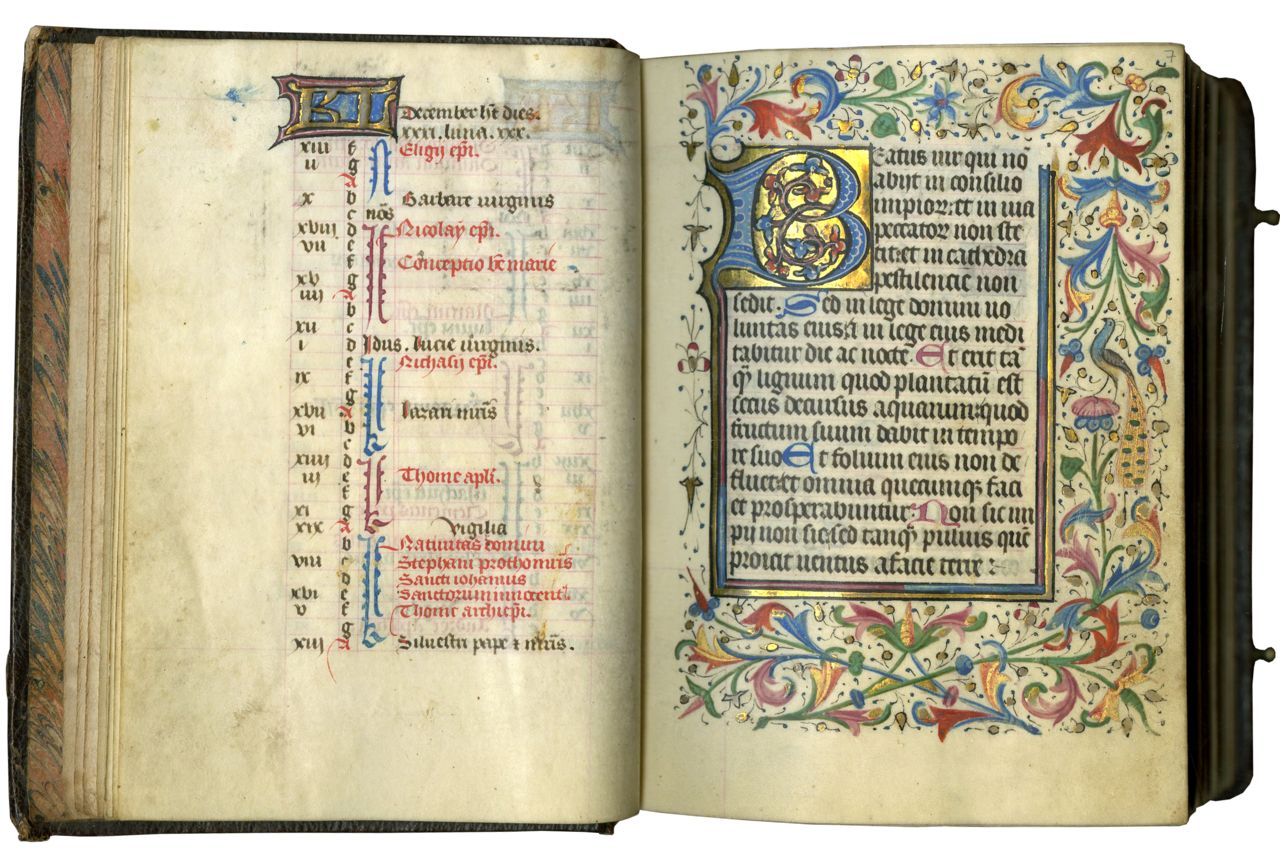

Marginalia also became more tailored to specific patrons in commissioned Books of Hours, devotional prayer books made for wealthy aristocrats. As society became more secularized so did manuscripts and the marginalia within them. Because marginalia was freer from censorship and religious constraints, it shows “‘folk culture’ in the form of riddles or pastimes,” most of which “would have depended on the region where the book was made” (Oatman-Stanford) (see fig. These are not the only two theories of the uses and purpose of marginal illustrations, Mary Carruthers suggests that marginalia served as a memory device to make pages specifically memorable in the place of page numbers.Īrtists were far less constrained by traditional imagery in the margins of manuscripts, and often let their imagination run wild, providing viewers with monstrous beasts, crude jokes, fanciful scenes, and wonderful peeks into the medieval mind. Some art historians have sought the iconographical connection between marginalia and the main context but, as Richard Randall will argue, there is more evidence that marginalia is not part of one “coherent program” (Randall 269). Many historians believe marginalia served to amuse the viewer and express the wit of the artist, providing manuscript pages with decorative additions. Medieval manuscript illuminations usually portrayed religious scenes to follow the sacred text, however marginalia is consistently secular in nature and often profane, satirical, or absurd (see fig. Many art historians believe that marginalia is nonsensical and disconnected from the main content of their corresponding pages, meant to amuse readers separately. Fools, musicians, exotic animals, hunts, dirty jokes, grotesque hybrids, obscenity, animals mimicking humans, humans in animal form, and mythical creatures fill the margins of medieval manuscripts seemingly “independent of the accompanying text” (Taylor 26) (see fig.

Marginalia “amplifies, comments on, or satirizes the more conventional and orthodox sacred and courtly meanings at the center of the manuscript,” providing viewers with bizarre scenes that provide a unique look into medieval life (Riess 535). Marginalia was most popular between the 12th and 14th centuries, before the invention of the printing press in Europe, while manuscripts were still crafted by hand. According the Kaitlin Manning, an associate at B & L Rootenberg Rare Books and Manuscripts, marginalia in a medieval context is considered illustrations that are outside of the page’s main content, generally in the margins (see fig. Before mass production of books brought literature to the masses, in medieval Europe the “educated elite hired artisans to craft these exquisitely detailed religious texts surrounded by all manner of illustrated commentary” called marginalia (Oatman-Stanford).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)